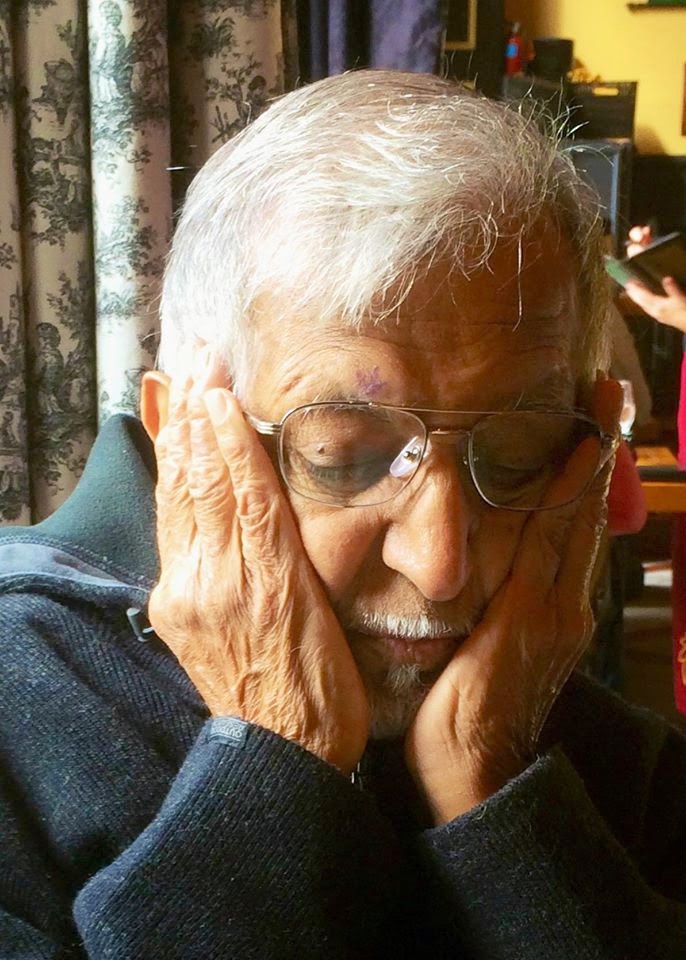

Last night, at 9:55, in a hospital room in Portland, my father took his last breath. I was sitting beside him on his bed. Shameem was standing beside him, my dear friend Nancy Boutin was with him. Nancy is a palliative care doctor and she knows about death, and she knew my father was making his passage. I, on the other hand, did not.

Last night, at 9:55, in a hospital room in Portland, my father took his last breath. I was sitting beside him on his bed. Shameem was standing beside him, my dear friend Nancy Boutin was with him. Nancy is a palliative care doctor and she knows about death, and she knew my father was making his passage. I, on the other hand, did not.

But my father has always been one to do things his way, and his death was no different.

He fell yesterday. He was heading home from the doctor’s office, when something happened and he fell. He fractured his pelvis, he hit his head, he bruised his shoulder. When he arrived at his condo, the people there could tell he was confused and got him into an ambulance. Shameem was called. I was called. We both raced to the hospital.

I was there by 12:30. Eight and a half hours later he was gone.

The doctors don’t know what took him. They only know that they were carrying out his explicit instructions to do nothing but provide comfort. My dad has been talking about his death for a while. He has been living with end stage kidney disease for more than a decade, and because he refused dialysis he had many other associated health problems. His big worry, though, was that he would be incapacitated, and require others to help him. He did not want that, and he did not want to trouble others. So when, at about 9:35, his breathing became labored, he was given 1 mg of morphine. “A whiff,” Nancy said.

The doctors don’t know what took him. They only know that they were carrying out his explicit instructions to do nothing but provide comfort. My dad has been talking about his death for a while. He has been living with end stage kidney disease for more than a decade, and because he refused dialysis he had many other associated health problems. His big worry, though, was that he would be incapacitated, and require others to help him. He did not want that, and he did not want to trouble others. So when, at about 9:35, his breathing became labored, he was given 1 mg of morphine. “A whiff,” Nancy said.

Nancy had arrived at my father’s side at ten minutes after nine. She talked with his nurse, his doctor, and then us. She told me he was dying soon, and I cried out NO! I did not believe it. I knew he refused treatment for the hematoma he had suffered from the fall, but doctors said we had a lot more time before that would effect him. And there was a chance it wouldn’t effect him. There was a chance that this time, like all the other near death walks my father has taken (Yellow Fever, Typhus, Malaria, the Plague, two horrendous car accidents, a broken neck, a brain infection, etc…) we would be shown a view of the ledge—but not taken over the cliff. Shameem and I had it all figured out. We would meet with his physicians in the morning, we would get them to his bed, and together we would urge him to rally.

“He’s decided,” Nancy said with a hug.

And he did. Less than an hour later he puffed out a few hard breaths then he opened his eyes and stared at something. I do not know what he was seeing. There were no words anymore. Not from him. It was just me and Shameem and Nancy, telling him we were there and that it was alright, and that we love him.

We love him so so much. So very, very much.

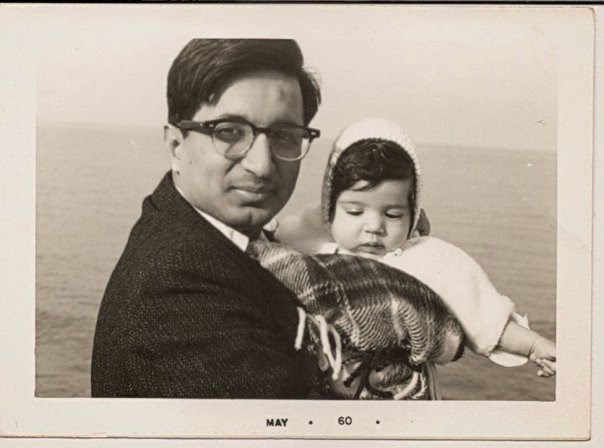

We were lucky, his family and friends. My dad was a jewel in the crown. Born in India in 1929 (we think, they didn’t keep records) he came to the US in 1950 for his education. He defied his family, and did not return to be handed off in an arranged marriage. Instead, he married a woman he met in Chicago, a German American who shared his love of opera and ballet. He defied the dogma of Islam in favor of the tangible qualities of numbers, and science. He defied conservatism by remaining an ardent liberal, always open to the potential of compassion. He defied his doctors, who said he should have died years ago because of his refusal to get dialysis, a procedure he refused in favor of daily exercise and meticulous attention to diet. He defied stereotype, and defied the idea that fathers are somehow less: less nurturing, less present, less aware. My father was always nurturing, always present, always aware. He was always there for me and my sister and brother and son and husband. He was there for his friends, and his relatives in India. No matter what time of day or night. He was always pointing to something for people to notice and think about and question. Always teaching us that there are things we can do that are kind. Even in death.

Life is all in our brain, he said yesterday. Everything we see and think and feel, all come from our brain.

Right now my brain feels like it is locked in a futile struggle to grasp the enormity of this loss. It’s just too big. For the rest of my life, I think, it will always be too big.

My father died yesterday, and I am proud of him for finding the exit he dreamed of. “The only way he could have done it better,” my brother Amir said, “is if he was protecting children from some terrorist.”

Dad would have laughed at that, and said it was true. We are a laughing family, my dad’s laughter, something that always made me happiest.

Goodbye, Dad. I will love you and love you and love you for the rest of my life.

January 15, 2015

My condolences to you and your family.

Cathy Russell

My condolences to you and your family Naseem.

Wow, Naseem–so heart felt and beautifully written, and in such a short time. I, too, will miss Mohammed. My condolences to you, Amir, Elijah, Chuck, and Shameen.

I'm very sorry for your loss, Naseem. My condolences to you and your family. Thank you for sharing your memories with all of us. It is a wonderful tribute to your father. All the best, Steve

Naseem – What a beautiful and heart felt write up of your father! I'm deeply sorry to hear of his passing. He was truly a gentle, generous, and genuine man that will be forever missed. I loved him so, and have fond memories which go back as far as his top floor condo on the Chicago lakefront. My condolences to yourself, Amir, Shameem, Chuck and Elijah. Please let me know if your plans include a service and/or burial in the Chicago area. Keeping you and your family in my prayers, Kathy Jenski

Yes, Naseem, I can tell you from personal experience that the loss of your parent will always feel too big to deal with. For me, I slowly became able to celebrate rather than mourn about the loss of my parent. I know you all will get there as well.

Lovely.

Naseem, I'm so sorry! It seems death always comes too soon. Your father was a beautiful man and his beauty lives on in your family and the many people he touched. I'm glad I had the privilege to meet him. Thank you for the exquisite tribute you shared. You all be in my thoughts in the days, weeks, months ahead of grieving, remembering, celebrating.

So sorry – a great man and a great family. May his wisdom guide you during this hard time. Love to the family.

Life and death are both too big! So beautifully written, Naseem. You've inspired me to write about my experience when my father passed last March. An incredible experience. So sorry for your loss-you are in my thoughts and prayers. So happy that you are surrounded by love as great as the Grand Canyon.

thank you for sharing this note honoring your father. your heart speaks so clearly. our love to you,

Rick and Harriet

Thanks for sharing these most personal thoughts. your dad was a prince.

Geoff

My love and prayers Naseem to you and your family. How blessed you are to have been loved and nurtured by your Father. He is still there with you blessing you and caring for you.

Thanks for sharing his life with us and the beautiful photographs. I'm so happy for you … happy you had such a wonderful father. You say you are soooo sad … I imagine the feeling to be penetrating, all encompassing, "present moment". You are sooo alive. I love you and will see you tomorrow.

Naseem, thank you for telling us. I'm so sorry, what a wrench has been thrown at you. Honestly, the plague?! With all your dad survived, it seems reasonable to think he would survive everything. I respect his values and send my condolences to your entire family and many friends today. I am sorry not to be able to join you. I'm there in spirit. – Becky in Eugene.

My dear, sweet, beautiful friend, I'm so sad to hear about your dad. I feel so grateful that I got the chance to meet him and experience his greatness. Please know I'm always here. Love you, Karen