|

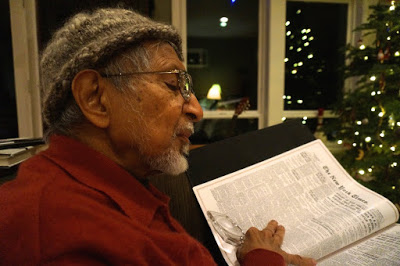

| Dad, last Christmas |

Last year on New Year’s Eve, Dad took Shameem, Chuck and I to his doctor so that we could hear a sobering truth: Dad was running out of time. Shameem, Chuck and I listened as Dad pressed the man to talk numbers. Dad wanted us to understand that he knew his life was coming to a close and that he did not want us to do anything to prolong it.

At the time, we three—Chuck, Shameem and I—thought the doctor was talking months, possibly a year. Maybe even more. Dad was an escape artist when it came to the Grim Reaper. In his life, he had slipped from the clutches of Malaria, Typhoid, Yellow Fever, The Black Plague. He had been in two nearly fatal car accidents, had broken his neck, survived a brain infection, and had been living with end stage kidney disease for more than a decade without dialysis. If Dad’s end was near, it would take its time. But my dad knew better. Off handedly he suggested he might be gone in two weeks. The doctor disagreed. Dad had much more time then that.

The meeting ended and we all shook hands and thanked the doctor. Thank you, thank you. Thank you very much. Afterwards, we went for lunch and watched Dad beam with the pleasure he always got from talking with his doctors. Dad’s relationships with these men and women were anything but simply professional. He would attend each appointment armed with folders filled with graphs of his weight, his blood pressure, his heart rate. Dad was a scientist and his failing health was his own study. He would read every article he could find on kidney disease, bone marrow, drugs, experiments. He studied graphs which would give him some idea, based on the trajectory of the numbers, when he might die. Sometimes those graphs would depress him. Sometimes they would energize him, giving him a sense of understanding and control. Occasionally, he was scarred. But visits with his doctors would bring him back to a solid place. After talking about his graphs and his latest blood work and all it meant the conversations would become a free for all, with Dad and Doc talking about all things in the universe, including the universe, its stars and planets, the earth and its atrocities and beauty: war, god, poverty, politics, food, opera, gangs, guns, you name it, Dad could speak to it. And did.

The meeting ended and we all shook hands and thanked the doctor. Thank you, thank you. Thank you very much. Afterwards, we went for lunch and watched Dad beam with the pleasure he always got from talking with his doctors. Dad’s relationships with these men and women were anything but simply professional. He would attend each appointment armed with folders filled with graphs of his weight, his blood pressure, his heart rate. Dad was a scientist and his failing health was his own study. He would read every article he could find on kidney disease, bone marrow, drugs, experiments. He studied graphs which would give him some idea, based on the trajectory of the numbers, when he might die. Sometimes those graphs would depress him. Sometimes they would energize him, giving him a sense of understanding and control. Occasionally, he was scarred. But visits with his doctors would bring him back to a solid place. After talking about his graphs and his latest blood work and all it meant the conversations would become a free for all, with Dad and Doc talking about all things in the universe, including the universe, its stars and planets, the earth and its atrocities and beauty: war, god, poverty, politics, food, opera, gangs, guns, you name it, Dad could speak to it. And did.

After lunch Dad asked if I had plans for New Year’s Eve, and I said no, we were spending it at home nice and quiet. We would listen to Portland’s All Classical’s annual countdown of people’s favorite music. It was a tradition, typically ending at midnight with Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, a piece of music I was taught to love at an early age when my parents would take me to the symphony, or as I would fall asleep to the sound of the radio playing in the living room.

When I told Dad we would stay home for New Years, I saw, felt, heard a sound of relief. Dad rarely imposed his desires, but clearly he was happy to know we would be together. And it was a beautiful night, ending with sparkling cider and Beethoven’s Chorale and Elijah and I conducting and everything—every little thing… being just right.

Then, two weeks later on January 14, 2014, Dad fell on the Portland streetcar. Ten hours later, he died.

And I think of all that today for obvious reasons. Anniversaries are sometimes a burden.

But I think Dad would be proud of his children: Naseem, Amir and Shameem. We have survived our first year of being orphans, and we have all come together for this holiday. We are carrying on the traditions that Mom and Dad started—the Catholic and Muslim agnostics who put up a Christmas tree not because they believed in a Christian god, but because they loved us, and what better reason could there possibly be?

|

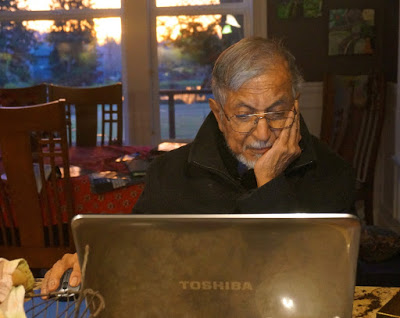

| Me and my Dad — Mohammed Allah Rakha |