The last words my mother ever said to me were, “Peer Gynt Suite. It’s the Peer Gynt Suite by Edvard Grieg.”

|

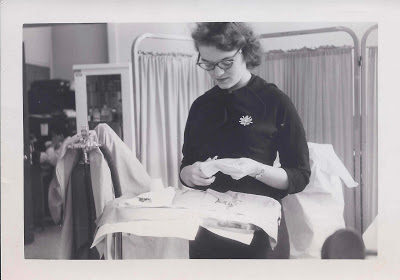

| Beverly Francis Rakha, right before my birth – 1959 |

I was in my parents’ car, my father driving home, my mother beside him, my four-year-old son and I in the back seat. It was rush hour, and it was a Chicago summer. Hot. Humid. Miserable. That was Mom’s word—miserable. She often used it to describe how she felt. And in the car on that day she was suddenly feeling “miserable.” Which meant, to me, only one thing: we would not stop at the Walgreens to pick up some things I hoped to get for my trip back home to Oregon. Instead, we would go straight back to my parent’s house and Elijah would have to do without trail mix or crayons on the long flight west. I sighed.

I was not patient with my mom’s miserableness. Not kind or sympathetic. My mom had been suffering with one ailment after another since I was twelve. Back then it was phlebitis, a potentially fatal blood clot was found buried in her lungs. I had come home from school to find no one home. A while later my dad called. “You have to be in charge,” he told me. Which meant feeding my younger sister and brother, keeping the house clean, the clothes washed and folded and put away. It also meant explaining that Mom would be okay. She will be okay. Right Dad? Dad didn’t know.

Mom did get okay. For a little while, at least. But then came the clots in her legs, then the ulcer that ended up eating up most her stomach, then the back problems which left her in the hospital for weeks on end in traction and on morphine. “The planes are flying so close to the window I can see the passengers. They have ashes on their face. Each one covered in ash.” And then there were the falls, the anemia, and finally—the diabetes.

“Do you have your pills with you?” I asked. She didn’t. “You’re suppose to carry them with you.” Chastising. Frustrated. Mean. Everything revolved around Mom and her health. Dad at her side. Retired from work, his new job was Mom. Blood sugar tests two, three times a day. Monitoring diet, monitoring blood pressure. Keeping records, logs. He had been an engineer. His new occupation kind of made sense.

I turned my attention back to my son. We were reading the book “Ferdinand the Bull.” It was a gift from my mom. Ferdinand is recruited to fight in the bull ring, an honor by all bull standards. But Ferdinand is not interested. He would rather spend his day out in the fields smelling the flowers. It’s a predictable gift from a woman who was always pointing out the flowers, the sculptures, the clouds, the music. Born in Chicago to Catholic German immigrants, tailors with little education, she rejected a line of parent-approved suitors to marry a Muslim man from India. Her parents did not approve. Neither did his. They married in a court house, no parents in attendance. Within a year I was born and by the time I was five I was in ballet class. Seven, piano. Every month we went to the orchestra. When the Bolshoi came to town, we went, never mind if we really couldn’t afford it.

I looked up from the book about the nonconformist bull. Something familiar was playing on the radio. As a child I would dance to it, scarves tied around my waste. Swirling color with me in the middle.

“What’s that playing?” I asked.

I watched my mother take a breath. “Peer Gynt Suite. It’s the Peer Gynt Suite by Edvard Grieg.”

She sounded tired. Exhausted. The long car ride. The traffic. The heat.

By the time we pulled into the driveway, my mom could barely get out of the car. “Low blood sugar,” I said, and Dad told me to go find the pills. “The pills” were sugar pills. Super-sized Smarties that can jolt a diabetic back to life. We got her in the house. Put one in her mouth. Waited.

A few minutes later dad got her a glass of orange juice, another fast acting sugar fix. He held it for her as she drank. “I’m fine,” she said to my dad. But she didn’t sound fine. She sounded like a drunk. She tried to get up, couldn’t. She pointed to the bathroom, and Dad took her there. A few minutes later he called for help. I stepped into the bathroom to find my father trying to hold my mother up. She had fallen off the toilet, her pants at her ankles. We lifted her up, I pulled up her pants. It was all happening fast. Too fast for me to understand that this was beyond low sugar. Too fast for me to think anything but “this isn’t good.”

I had never seen Mom in a full blown diabetic attack. “Is this what happens?” I asked my dad. “Is this normal? Should we call her doctor?” He looked frightened. We laid her on the couch. My son stook at his Grandma’s side.

Elijah is her only grandchild. She had been looking forward to our summer visit like a kid in a countdown to Christmas. “Only one more month…Just two more weeks…Just five more days…” “Grandma?” Elijah said. “You better now, Grandma? No more miserable?” She smiled at her grandson, and that’s when my father and I knew.

Not low blood sugar. At least not just low blood sugar.

Dad grabbed the phone. Ten minutes later, paramedics put Mom on a stretcher then rolled her into the ambulance. My son and I got back in my parents’ the car, followed behind the fire truck, which was followed behind the ambulance, which had my mother and father. My father sitting beside her, I was sure. My father was always beside my mother.

It was a hemorrhagic stroke, a catastrophic explosion deep in my mom’s brain. If we had got her to the hospital sooner, turned around in the driveway perhaps. Better yet, had we raced to a hospital as soon as she said she didn’t feel well. Paid attention. Had we listened. Asked questions….

“The bleed is massive,” the doctor pointed to a scan. He laid out our options. Put in a drain, try to get out the blood. Or—do nothing. The drain may help, but it won’t make my mom better. “Too much damage for that.” Doing nothing would mean she would die, “in two or three days.”

My sister arrived. My brother. Both of them driving halfway across the country in eighteen hours. Mom is in the hospital’s hospice. Private room, big windows, quiet, plenty of space for the family to sit around the bed. Dab her lips, talk to her. See if there is any response. Anything at all.

Dad sends one of us home for her Walkman. We put in a cassette. Music plays. We tell each other we’ve made the right decision. Survival would not be what Mom would want, we say. Not if she couldn’t move. Not if she couldn’t feed herself, or bathe. Not if she couldn’t tell us what piece of music was playing.

I think of this now as I sit on my porch in Chautauqua and listen to the Orchestra practice for this evening’s performance of the Peer Gynt Suite. I didn’t recognize it at first. But then the memory came. Not the one in the car, but the one in the living room, me dressed in my mom’s scarves. My mom and dad came to Chautauqua with me once. They loved it. The music. The dance, the lectures about all the things they cared about. Society, culture, science, fairness, hope.

My dad moved to Portland shortly after my mom died. He is eighty-four years old now. During the day, when he is not watching the news, he is listening to KBPS, Portland’s “All Classical” station. He listens to one piece after another, always waiting for Mom to tell him what is playing. “I wait and I wait,” he says, “but she never comes.”

Naseem Rakha 7/24/13

Coda: My dear friend Joe just sent me this link to the Peer Gynt Suite. My mom would have loved to have been on this train.

My second time into the Vietnam war, as a diving officer in the Mekong Delta including the Cambodia Invasion, 17, then 35 men on my boat and responsible for I knew not what at age 24, I crashed. My wife back home disappeared, finally found in Berkeley CA shacked up with some guy, and some other guy I never heard of wrecked my cherished MGB. My insurance company charged me, in Vietnam hell, with the accident on my record. My parents divorced, "Stars and Stripes" made sure we were well aware of the way Vietnam vets were treated in the states, and my lifelong trust in my country's soul felt like a stupid, primitive vulnerability.

But I had a Sony reel-to-reel; we all did from the Navy Exchange, and headphones, and on it was "The Peer Gynt Suite." That might have been the difference between living and not.

Thanks for the reminder what music can be, Naseem.

Beautiful writing, Naseem. As always. Now the Grand Canyon setting makes even more sense.

So beautiful and poignant. I listened to Solveig's Lied and thought of you all.

My first 2 CDs were Peer Gynt and Sheherezade. Today I have multiple versions of each.